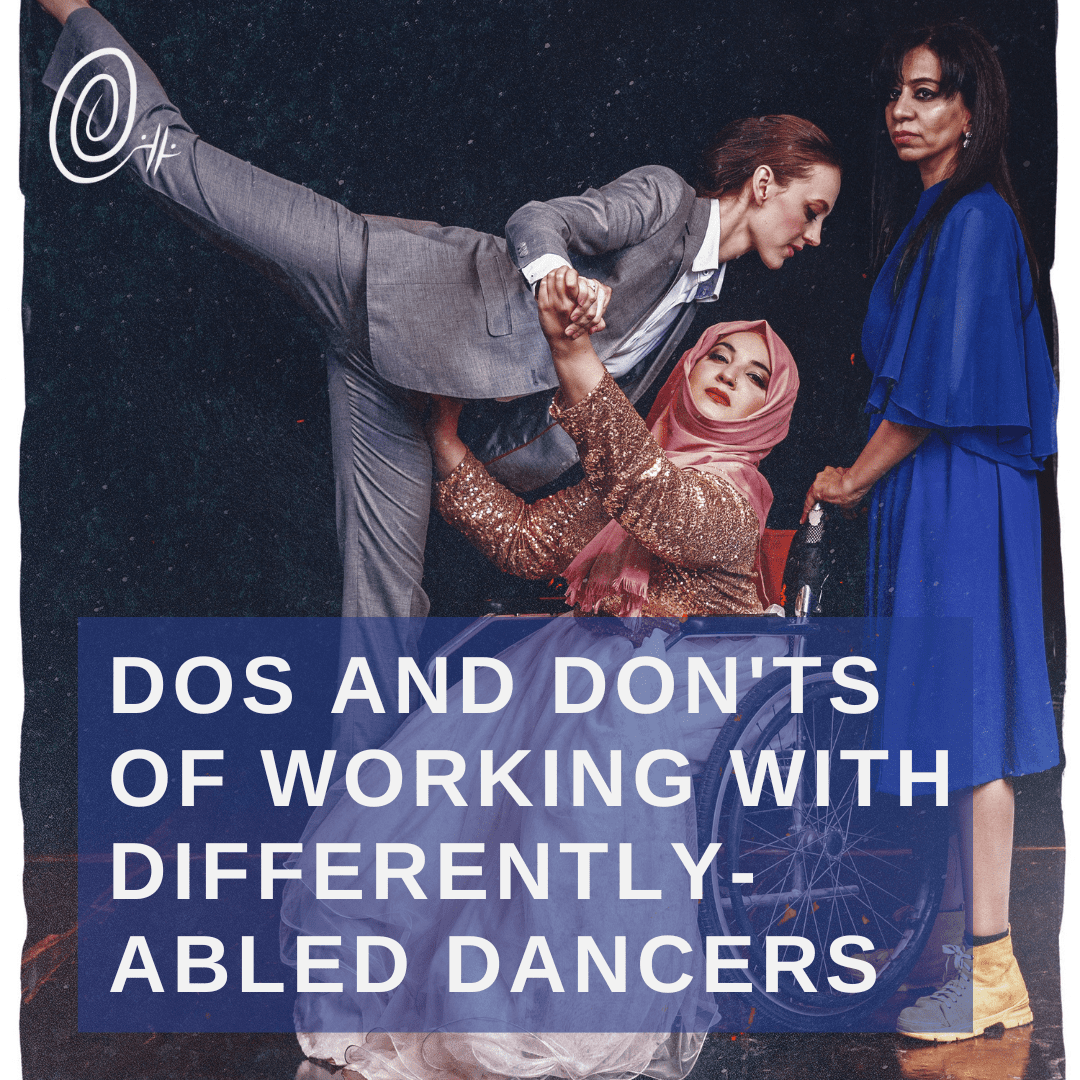

Dos and Don’ts of Working With Disabled Dancers

When I lived in Seoul, I trained and performed with a company that regularly worked with disabled dancers, and helped coordinate one of their initiatives, the Korea International Accessible Dance Festival. Here in Pakistan, I’ve done a few projects with differently abled dancers, in particular More Than My Gender and multiple collaborations with visual and performing artist Sarah Mumtaz. Throughout these experiences I’ve had the opportunity to see a variety of work, and I’ve assembled some dos and don’ts for anyone considering ways to be more inclusive and accessible in dance.

Before we get started, I’d just like to note that there is every reason to include disabled and differently-abled dancers, whatever their specific situation is. Somehow dance gets very high and mighty about tradition and technique and clutches its pearls whenever anyone messes with it. While dance as a field is constantly evolving, the institution of dance has been very slow to do anything about its traditionally exclusive, white, western, able-bodied preferences.

My point is, it’s all well and good to go on and on about how dance demands virtuosity – to which I ask you about Yvonne Rainer and the postmodernists, who did everything they could to make dance not virtuosic, or the whole performance art and happenings movement. That passes because of its white and western origin, but the heart of the matter is that dance is about exploring movement and questioning what meaning can be made from that, and this is something that all people can do.

I’ll get off my soapbox now. Let’s get into the dos and don’ts.

Don’t make it about the disability

One of the most wonderful pieces I’ve seen to date (and that doesn’t include a clause around ‘by differently abled dancers’) was at the Korea International Accessible Dance Festival. It was a duet with two women – one was in a wheelchair and one had a prosthetic leg removable below the knee. The movement obviously acknowledged and used both, as you would with any main object, prop, or other accessory in a dance performance, but the piece wasn’t about their disability. It was just a duet, beautiful, well-crafted, well-performed, and interesting.

This piece is single-handedly responsible for opening my eyes to this world of accessible dance and inclusive dance. I hadn’t thought much about it before, to be honest, and had all the same misconceptions that probably most people do. But this piece to me was a shining example of what accessible dance should be and could be.

When I compared it to another piece at the same festival, where the one able-bodied dancer (and choreographer) was the main character and hero, and the story was all about how they were saving or helping or doing wonderful things by inviting the differently-abled dancers to join them…well. Let’s just say the difference was pretty stark.

You don’t need to make the piece about the different abilities. It doesn’t need to be about that person’s situation in particular. It doesn’t need to highlight or diminish the dancer’s ability. You can actually just make a dance piece that uses movement appropriate for the different body types performing it.

Don’t patronize or gloat

I touched on this a bit in the earlier section, but it’s important enough to say again. Listen: nobody’s better because they can do certain technical things or spin many times. You don’t need to get high and mighty because you are ‘doing good’ or ‘giving opportunities’ or whatever. Just do the work and be a decent person.

I can’t remember the specifics of that second piece I mentioned above, exactly what was the story. What I do remember, though, is how slimy it made me feel afterwards. It was self-congratulatory and narcissistic, and used the dancers as moral capital.

Accessible dance works when it goes first to the movement and the collaboration. That leads me to the dos.

Do collaborate

When I choreograph for new dancers, one of the first things I do is try a variety of movement and see how they move. This lets me know what movement works best for them and how I can use their style to tell the story.

That’s exactly how I approach working with differently-abled dancers as well. They know their abilities better than me, and so by working together, we can find the movement that’s going to work best, that will look the best.

Additionally – and I feel like this should go absolutely without saying – but if you usually collaborate creatively with your dancers (and I think you should), then you should do the same with differently-abled dancers. When I work with Sarah Mumtaz, for example, she always makes my ideas better. I think there is a stigma and misconception that because differently-abled dancers can’t always do the traditional forms, that they don’t have anything to say or offer on movement, and this is utterly wrong. Collaborate, share, and explore, and the piece will be better.

Do explore and experiment

You don’t need to treat differently-abled dancers as fragile or strange creatures. Again, this should go without saying, but I had to deal with all my own biases and so I’m sharing it here in case it helps someone who, like me, grew up in the ballet world and got to their mid-twenties without even knowing that accessible dance was a thing.

One of the first things I did when I started working with Sarah was experiment with all kinds of movement. Sarah loves to explore as well, and so we spent a lot of time just seeing what she could do. I would show her something, whether or not either of us thought it’d be possible, and we’d see how it worked. Likewise, when I was choreographing the duet that I have in More Than My Gender with Tanzila Khan, who is in a wheelchair, we spent at least a few rehearsals with me carefully climbing on and around her to see what might be possible.

Don’t assume you know everything that will work or not – you might be surprised. Take the time to explore and experiment. Think of different concepts and different ideas. The most wonderful part about working with diverse dancers is the new ideas and perspectives that you gain, so don’t just bash in and assume you know everything.

Accessible dance can be wonderful, and it can also be awful and condescending. A lot of it depends on how you, as dancer or choreographer or both, approach it. I hope these tips encourage you to expand your understanding of dance and give you the tools to respectfully bring in diverse dancers.