An American Dancer in Pakistan, Volume 4

Before I came to Pakistan, I really had no idea what I was going to do. Of the four months I was initially planning to stay, I had one week of schedules, and a few nebulous half-possibilities. I just had the word of a friend, and my own gut feeling, that there was something to find.

I already knew that I’d have to be on my toes to handle this year of uncertainty, and I would need everything I’ve learned on how to move fast and how to let go quickly.

In many ways, I can’t say I’m surprised by what I found, because I’m not. I’ve lived in what the American President would call “shithole countries” for long enough to know that representation and reality are very different. I was not expecting the Pakistan my friends were afraid of.

Even so, I couldn’t have predicted where I’d find myself.

One day, my friend said to me, “Oh by the way, we’re dancing for my friend’s wedding.”

It didn’t seem to be a request, so I didn’t argue. Dance is a huge part of a wedding, as one of the three days of the ceremony — the “mehndi” — is dedicated to dance. The fancier weddings hire choreographers and professional performers to make a slick concert-style performance. Others simply recruit hapless friends and family to try and make something.

This particular wedding was the latter, and I was one of the hapless friends. Because I can think of movements easily and remember quickly, I ended up choreographing a few songs and steering some of the rehearsals. A few other songs were choreographed by another hapless friend, who moonlights as a dancer when he’s not working a bank.

In the end, we had 7 songs (though just 1–2 minute clips of each). The event is set up like a dance battle, with the groom’s side and bride’s side taking turns. The set up was flashy and bright, smart lights blinking wild colors and strobes.

There was nothing “professional” about it, and there is still a strange dichotomy between this acceptable form of dance and stage performance. Still, it was a night to celebrate dance, and performance, in whatever small way — and that, to me, is something in itself.

Another day, a different friend texted me to ask if I wanted to collaborate on a piece as part of the Lahore Biennale. This was the first year of the Biennale, a city wide festival of art. The opening was a musical performance at a mosque in the old city, and the old Lahore fort was filled with art installments. The first edition was supposed to be last year, but there were too many problems. Even though it was controversial, the city was at last ready to host it this year.

Our performance was for the opening of a gallery, a repurposed room in an abandoned factory. The subject of the show was on gender. Rehan and I put together the piece in the space of a week, blending his slow, meditative version of kathak with my twisting, balletic modern. We didn’t try to mix the styles, just place them next to each other, and came together at the very end. Somehow it became a metaphor of a peaceful east vs west meeting.

It was a simple piece, but beautiful, and people were effusive in their praise on it. Rehan and I agreed we’d have to come back to it, and extend it.

After some months of trying to get in touch with the National College of Arts, I was finally able to talk to someone and arrange for a visit to meet some of the student societies.

The student societies, particularly those in the performing arts, come together twice a year to prepare performances for the incoming class. They have societies for traditional mime, fusion mime, theatre, comedy, sketch, choir, dance, and more.

From 5–7pm during this time, the student societies take over the campus. Just walking through the labyrinth of red brick buildings, everywhere there were groups of students doing theatrical games and improvisations, many of which I’ve done before.

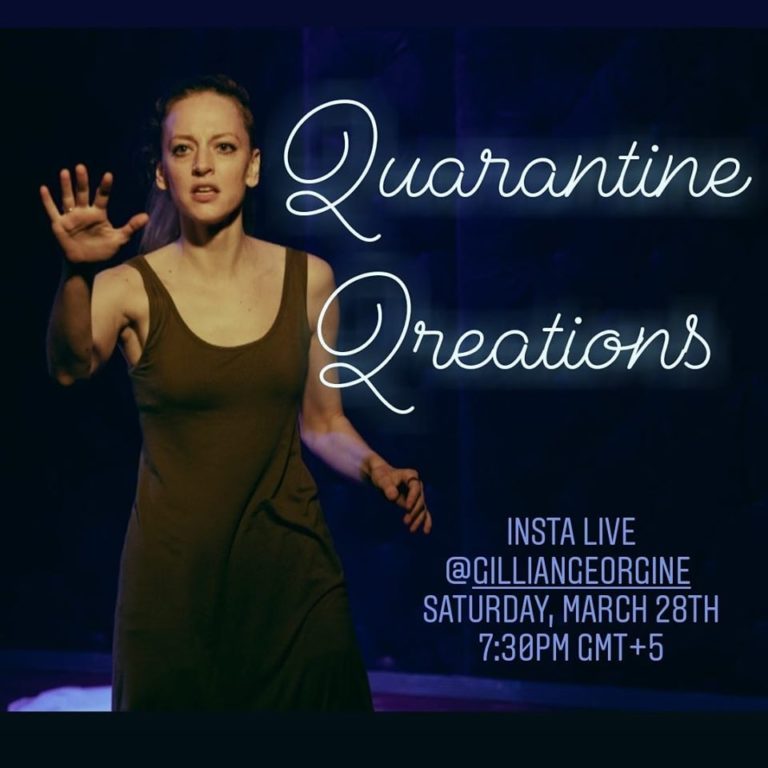

I spent the time with the dance society, teaching contemporary phrases and offering my thoughts on their work — after a very awkward beginning when the director dropped me off and said, “This is Gillian, she can help you.” While I felt strange about crashing their rehearsal, I started by watching and talking to the student in charge, until they asked me to teach something.

There were eight or nine students in the society. They were earnest and studious, though I wasn’t quite sure what to think about the very hierarchical structure of the society where 1–2 people take charge and act as “teachers,” while the others are “students.”

Still, they were all receptive and interested in what I had to teach, and showed off their own styles remarkably un self-consciously. I don’t often find that in college students, and was impressed. Just in watching the games the societies play, it was clear they were used to and comfortable with performing.

People say there is no art here, it’s not acceptable, the government is always trying to ban dance in schools. The latter two sentences are true, and no doubt the small section of the population I’ve seen in these examples is a tiny percentage.

And yet, here it is. It exists, and it is vibrant in its own ways. There are few outlets to learn and grow, and the people who are in it are hungry to learn.

Perhaps that’s why, at a recent performance I was attending, someone came up to me. He said he’d seen my performances with Rehan and at Goonj, and asked me to stay longer in Pakistan and teach. His sentiments have been echoed numerous times since then, and while it may be only a few people, it means something to me.

It’s not that I’m surprised there’s stuff to do here. But I have been surprised by the depth and vibrancy of it. Indeed, it is small, but small does not need to mean insignificant.

Stay tuned for more updates from Lahore!